When I was a teenager, I struggled with the concept of normalcy and my feelings toward it. I wanted to fit in with the crowd, which at many times resulted in angst over whether or not I was able to be or was being myself. I participated in some activities I didn't feel particularly interested in, because the friends or classmates I wanted to impress or imitate did them. I didn't know what to contribute to group conversations, because many of the things I felt comfortable speaking about--books, the experience of being a minority in the US, my frustration with academic competitiveness--often led to conversational dead ends. I was constantly struggling with being just good enough to be recognized and given opportunities for further personal development, and not receiving the sneering condemnation of my peers.

I'm sure many can relate.

The concept of "normal" was a mystifying one, made even stranger when I took AP Statistics. In studying averages, I thought about how arbitrary "normal" is. One of our main concerns in our teenage years is to be accepted by our peers--to be "normal." But this "normalcy" to which we strive rarely exists in a pure, attainable form: it is an invention of the faceless mass of society that conforms our expectations, goals, and perceptions of ourselves as inadequate. Much as the mean of a set of numbers (that's the number you get when you add up all the numbers in the set and divide it by the number of numbers in the set) sometimes doesn't even appear in the set itself (example: the mean of 1, 2, 9, and 10 is 5.5, which isn't a number in the set), so the norm is basically nonexistent if you try to point to a single individual as a exact representation of the norm in a crowd. (That last part is basically what applied statistics is all about. Don't you wish I had written this post before your AP test?) I'm sure most of us can think of the high school classmate whose social grace and overall peer acceptance we envied--but there's a good chance that that classmate would think of someone else if asked to do the same, and so on. No one thinks of him- or herself as the norm.

In effect, I was trying to be a concept that rarely ever existed in a crowd. I was part of the 99.99% trying to be the 0.01%.

If so many people are unique, not "normal," how meaningless it is of us to wish to be the norm.

At 23, I have long passed my teenage years, even if I didn't know when it happened--but I struggle with another concept now: that of being an adult. I don't feel like an "adult" at all. What does that mean, anyway? Does it mean working a passionless day job and saying a passionless prayer for the fact that I have a job? Does it mean marrying my long-time partner because marriage is what you're supposed to do at or by a certain point? Does it mean Sunday night spaghetti dinners, dinner talk about how work or school went, and routine sex on Friday nights? How does society define an adult, and how can I define the term myself so that I am comfortable with it?

The concept of being an adult is just like the concept of being normal--societal pressure to conform to a standard that no one can exactly define--which is why I find the idea that people will "outgrow YA in time" so laughable. Again and again I make the point that being an adult isn't necessarily better than being a teenager. I've met a lot of adults who I think are a waste of space, and many teenagers who I think should be heard by more people. If you replaced all the US Congressmen with a similarly powerful group of teenagers, I think there's a chance that a lot more things could be done.

This is what critics of the genre of YA lit don't get. "YA" is not a measure of quality. Your lifestyle is not necessarily better than mine; what right do you have to try and impose your lifestyle on mine? Don't tell YA readers that they're just going through a phase. Don't tell John Green and Melina Marchetta they'll be legitimate authors when they finally write adult books. Don't say people can't learn anything from reading escapist literature.

Why aspire to be "adult," to be "normal"--to be "them"--when it's better to strive to be the best me that I can be?

While I use terms such as "teenagers" and "adolescents" in my reviews, in no way would I consider myself its figurative antithesis, the adult. I am simply me, and I am on an ever-changing spectrum. Sometimes parts of me overlap with parts of others, resulting in similar interests and values. Other times parts of me differ from parts of others, and those are called unique qualities. That's my definition of personhood, irrespective of age labels. As long as I don't kill people and treat my fellow human beings like human beings, and as long as I remember that at no point in my life will I have learned everything there is to learn, then I'm proud of being myself and not trying to be someone else.

Age categories and other black-and-white labels are becoming more and more archaic. One's maturity lies on a spectrum, not in a series of stiff, unidirectional stages. YA literature can be read, enjoyed, and respected by anyone. If you tell someone they can't do or read something because it's not "normal" or it's not what an "adult" would read and that doing or reading so will limit my thinking or being, well, besides for thinking that you are a close-minded being, I am not really limited at all.

Showing posts with label YA lit issues. Show all posts

Showing posts with label YA lit issues. Show all posts

Friday, July 13, 2012

Saturday, June 4, 2011

The Only Thing I Really Hate

World, I am at a loss for what to say or do. This article appeared on the Wall Street Journal website today, yet another in a neverending line of articles appearing in esteemed publications that condemn young adult literature. It says nothing new, really, just the usual bunch of accusations against the genre, namely that YA literature encourages the spread of dangerous activities such as sexual exploration, self-injury, anorexia, etc. The author, a Meghan Cox Gurdon, suggests that the proliferation of "dark YA" on the shelves these days creates adolescent with darker minds, impulses, and desires.

Articles like this one, of course, can't exist long in the world before the online YA community rises up to the occasion. Seriously, we're probably one of the most well organized informational armies out there. Twitter is like our right hand, and online communication reigns in the YA world because YA is still a not-very-widely accepted part of our culture that requires our "going underground," or "taking to the ethernets," to find "our people." YA authors, bloggers, librarians, publishing professionals, and more have been tweeting Wall Street Journal (@WSJ) nonstop. Libba Bray wrote an encore-deserving series of tweets that have been republished by WSJ as a "letter to the editor." And on and on and on.

Again, there's not much being said that hasn't been said before, so I want to focus on what I believe is the real "enemy" here: the attack on change and progress, and the lack of openmindedness.

Furors regarding YA-condemning articles and the online backlash from the YA community remind me of dramatic court or political scenes where representatives from both sides just kind of stand face-to-face and talk quickly and at the top of their lungs while stuffing their ears and singing "lalalalalalalalala" in their heads. Scenes like this drive me crazy not because of WHAT is being debated, but HOW it is being done. They talk and talk, and we talk and talk, and it seems like nothing has changed because the same arguments are being made every time on top of the fact that neither side is willing to actually listen to the other. No, each side is preoccupied with their belief of the "rightness" of their position, and even as they claim to be listening to the other side, they are in fact busily constructing counter-arguments for what they are "listening" to at that very moment. This is the nature of debate: you pick a side, and by all hell's fiery rivers, you stick to it, gosh darnit.

What we need is discourse, which is the meeting of the parties on an equal plane in which both parties are willing hear the other's points with an open and innovative mind, to compromise if needed, and to create something new out of what's already there. Debate doesn't create anything new because it's too busy standing its ground: there is one winner and one loser. But in discourse, the answer arises from something that has never been there before, and that, over debate, is how progress gets made.

Technically I am well past the age range in which reading YA is considered acceptable. But I have never felt like I have grown out of YA, just like some people have never felt like they needed or wanted to read YA. YA is still my preferred literary genre not because of the content of the books, or the books' messages, but because of how these subjects are approached. It's because YA is the state of mind in which I have experienced the most openmindedness, the most support for innovation and creativity and progress. I love the YA mindset because it's dramatic, because it's crazy and fun and wild and unpredictable and a little scary at times... because it is always, always, always open to and searching for new possibilities.

I have come to realize in the past year that there is really only one thing that I hate, in its myriad of manifestations: I hate willful ignorance, and closemindedness, and the determined denial to see things as black and white and dismiss even the possibility that things might be gray. What the hell is really black and white in this world, besides for a chess board and a zebra? Reducing things--anything, everything--to dichotomies is a small-minded, judgmental, and uninformed way of thinking, no matter how many education degrees you've earned or awards you've received. Years don't make maturity; the length of your CV doesn't denote your amount of wisdom. Maturity and wisdom is gained through the experiencing of life through clear and permeable lenses, of keeping your mind open to new ideas and of constantly adapting yourself to an everchanging world.

Sometimes I miss the old days, too. Every time I read L. M. Montgomery's Anne series, I can't help but think that life would be so wonderful if I could be Anne. But my wishing for that is the same as these YA lit condemners bemoaning the "loss of innocence" in adolescence these days: there's no use in trying to make something go back to the way it used to be. There is only going forward.

Articles like the WSJ one don't just attack YA literature: they also attack the intelligence of young adults and YA readers, the act of reading, and the very institution of education and learning itself. The article is an attack on progress above all. When I read an article such as this one, I'm offended on behalf of the YA community, but I'm also offended on behalf of the human race. The natural state of things is entropy: to try to force things to stay as they always were is unnatural and, ultimately, harmful. Everything is always taken to a whole other level when it deals with young people because growing up is the ultimate metaphor for change and progress. We want things to turn out one way, try to shape things so that they do, but things are always out of our control, always moving forward. No one helps a person with a broken leg heal by keeping him/her off his/her feet forever and ever; no, physical therapy is involved, the gentle guidance to let the muscles become aware of its own abilities to heal.

I am hopeful of things turning out alright for YA lit. Civil, women's, LGBT rights--it's been an uphill climb for all of these movements, but no matter how loudly the naysayers cry, the world knows that the natural order of things is change.

Articles like this one, of course, can't exist long in the world before the online YA community rises up to the occasion. Seriously, we're probably one of the most well organized informational armies out there. Twitter is like our right hand, and online communication reigns in the YA world because YA is still a not-very-widely accepted part of our culture that requires our "going underground," or "taking to the ethernets," to find "our people." YA authors, bloggers, librarians, publishing professionals, and more have been tweeting Wall Street Journal (@WSJ) nonstop. Libba Bray wrote an encore-deserving series of tweets that have been republished by WSJ as a "letter to the editor." And on and on and on.

Again, there's not much being said that hasn't been said before, so I want to focus on what I believe is the real "enemy" here: the attack on change and progress, and the lack of openmindedness.

Furors regarding YA-condemning articles and the online backlash from the YA community remind me of dramatic court or political scenes where representatives from both sides just kind of stand face-to-face and talk quickly and at the top of their lungs while stuffing their ears and singing "lalalalalalalalala" in their heads. Scenes like this drive me crazy not because of WHAT is being debated, but HOW it is being done. They talk and talk, and we talk and talk, and it seems like nothing has changed because the same arguments are being made every time on top of the fact that neither side is willing to actually listen to the other. No, each side is preoccupied with their belief of the "rightness" of their position, and even as they claim to be listening to the other side, they are in fact busily constructing counter-arguments for what they are "listening" to at that very moment. This is the nature of debate: you pick a side, and by all hell's fiery rivers, you stick to it, gosh darnit.

What we need is discourse, which is the meeting of the parties on an equal plane in which both parties are willing hear the other's points with an open and innovative mind, to compromise if needed, and to create something new out of what's already there. Debate doesn't create anything new because it's too busy standing its ground: there is one winner and one loser. But in discourse, the answer arises from something that has never been there before, and that, over debate, is how progress gets made.

Technically I am well past the age range in which reading YA is considered acceptable. But I have never felt like I have grown out of YA, just like some people have never felt like they needed or wanted to read YA. YA is still my preferred literary genre not because of the content of the books, or the books' messages, but because of how these subjects are approached. It's because YA is the state of mind in which I have experienced the most openmindedness, the most support for innovation and creativity and progress. I love the YA mindset because it's dramatic, because it's crazy and fun and wild and unpredictable and a little scary at times... because it is always, always, always open to and searching for new possibilities.

I have come to realize in the past year that there is really only one thing that I hate, in its myriad of manifestations: I hate willful ignorance, and closemindedness, and the determined denial to see things as black and white and dismiss even the possibility that things might be gray. What the hell is really black and white in this world, besides for a chess board and a zebra? Reducing things--anything, everything--to dichotomies is a small-minded, judgmental, and uninformed way of thinking, no matter how many education degrees you've earned or awards you've received. Years don't make maturity; the length of your CV doesn't denote your amount of wisdom. Maturity and wisdom is gained through the experiencing of life through clear and permeable lenses, of keeping your mind open to new ideas and of constantly adapting yourself to an everchanging world.

Sometimes I miss the old days, too. Every time I read L. M. Montgomery's Anne series, I can't help but think that life would be so wonderful if I could be Anne. But my wishing for that is the same as these YA lit condemners bemoaning the "loss of innocence" in adolescence these days: there's no use in trying to make something go back to the way it used to be. There is only going forward.

Articles like the WSJ one don't just attack YA literature: they also attack the intelligence of young adults and YA readers, the act of reading, and the very institution of education and learning itself. The article is an attack on progress above all. When I read an article such as this one, I'm offended on behalf of the YA community, but I'm also offended on behalf of the human race. The natural state of things is entropy: to try to force things to stay as they always were is unnatural and, ultimately, harmful. Everything is always taken to a whole other level when it deals with young people because growing up is the ultimate metaphor for change and progress. We want things to turn out one way, try to shape things so that they do, but things are always out of our control, always moving forward. No one helps a person with a broken leg heal by keeping him/her off his/her feet forever and ever; no, physical therapy is involved, the gentle guidance to let the muscles become aware of its own abilities to heal.

I am hopeful of things turning out alright for YA lit. Civil, women's, LGBT rights--it's been an uphill climb for all of these movements, but no matter how loudly the naysayers cry, the world knows that the natural order of things is change.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Why I Want More Asians on YA Book Covers: My Experience with Racism

|

| AHAC.org |

I was in early middle school, 6th, 7th grade, maybe. My family had gone out to the all-you-can-eat buffet lunch at Pizza Hut with several other families. We were all close, due to similar cultural extracurricular activities and the same age range for the children. We kids chowed down our pizzas, breadsticks, and sodas, hungry rascals that we were, and began to get restless while the adults ate leisurely and chatted with one another. I pulled out a deck of cards and engaged some of the others in a game, but 52 cards is not enough to entertain 15 or so kids, and so inevitably there was lots of running, shouting, and being hyper kids at a pizza parlor.

So kids were running around and we were all in general making a lot of noises when one of the mothers caught some of the kids as they raced by the tables for the fifth or so time. "Settle down!" she ordered us in Chinese. "We're the minority, we have to be quiet!"

Now.

In her defense, rowdy kids in a restaurant should definitely be taught to be more considerate of other patrons and their surroundings, even in a family-oriented location.

Aaaaand that's about all I can say for her argument.

I was shocked. Seething with anger. Humiliated for my own race. Disappointed that someone so well educated, so well respected amongst our community, so looked up to by me and others, would say such a thing to kids, teach us, even unintentionally, that this sort of subservient inferiority thinking is acceptable. It's been probably 10 years since the incident, and my heart still clenches whenever I think of it, that day when I lost respect for someone I admired, that day someone--someone of my own race, no less--took my racial identity and slammed it in my face, pressuring me to conform to "acceptable" behavior and beliefs for my race.

Perhaps one might argue that being Asian is not quite as "difficult" as being a member of another race or ethnicity. Asians are considered to be in a similar position as Jews in many ways in American society. We have light skin, generally perform well in school, and obey rules; a large percentage of Asians live in comfortable socioeconomic brackets. To many, Asians do not come to mind when the word "minority" and its stereotypical implications arise. In fact, Asians were held up as the "model minority" back in the fifties and sixties, as an example of what minorities can accomplish if only they put themselves into it and stopped blaming society and situation for their troubles. [Edited to fix ambiguous statements that could've been misconstrued. Thank you, Linda!]

But what we, over many other racial and ethnic groups, have acquired is a passive acceptance of the beliefs and treatment others subject us to. Many Asians do not have that much of a problem being considered the nerd-smart, obedient, socially awkward race. Better than being considered the hoodlum, or the troublemaker, or the good-for-nothing...right? It is, however, our own quiet acceptance of others' assumptions of what our race is like that ensures our position as a racial doormat.

The problem is that Asians self-perpetuate these beliefs of obeisance, one generation after another. The family friend at the pizza restaurant tells us kids to be quiet because we're the minority, thus we shouldn't attract attention to ourselves. She acknowledged that we may be disturbing the other restaurant patrons, but instead placed the responsibility on society's expectations of our race to be meek and complacent. A white mother would've said to her rowdy white kids, "Settle down! You're in a restaurant, not a park. Don't disturb the other patrons with your noise." Her argument is much more situational and individualistic. The kids are held accountable for their own behavior, not the image of an entire race.

I realize there are cultural discrepancies in these two mothers' different reactions to their disruptive kids. You know, East vs. West, collectivism vs. individualism, the sort of thing you study in psych, history, or soc-anth classes. But if we--and by "we" I don't mean just Asians, but everyone else in this whole damn world--continue to allow this racial self-policing to continue, then it's no wonder that white values continue to be considered superior, preferred. It's no wonder that Asians get pigeonholed into certain "types" of personalities and careers, and no wonder that some Asians' backlash to their own culture is so striking and self-hating. It's no wonder that Asian models get taken off the covers of Asian-set or Asian-themed books.

|

| I encourage you to click to enlarge this image so you can check out the words below "Olive Crown." |

And whereas you can walk into a school and see groups of black or Latina ladies expressing their pride at being black or Latina, you don't find the same with groups of Asian friends. Asian girls will typically flaunt their Asianness in a subconscious subjection to archaic Orientalist attitudes. Their thinking is, "I'm glad I'm Asian because I have great hair / age well / guys of all races think I'm cute." It's not, "I'm proud to be Asian for me and ME ALONE" the way black women can often say so about their race. Asians are constantly thinking of themselves in terms of other people. And yes, that's part of our Eastern culture as well, this attention to interpersonal connections as the primary way of validation of self, but that absolutely does not give other races and ethnicities the right to walk all over us.

The lack of Asians on book covers enforces the idea that Asians should be the quiet race. Because we are not the proud stars of our own stories, but rather the spectators and secondary characters to others'. We are always the best friend, never the protagonist. When I look at book covers featuring white models representing protagonists that I end up loving and relating to, I subconsciously associate myself with these white characters. It is my "Twinkie-ness" (yellow on the outside, white on the inside) that allows me to enjoy YA books. Reading YA lit the way it's currently jacketed takes away from my Asian identity, because both white society and my own Asian one do not allow for Asians to take a starring role.

Large chain bookstores would not buy Cindy Pon's Silver Phoenix because there was a proud Asian model in traditional Chinese garb on the cover. It's a beautiful, stunning, breath-taking cover, one that had me lusting after it for the fact that it had an Asian girl on the cover alone. Replacing the gorgeous, racially correct cover with a racially ambiguous, awkwardly posed and accessorized Darkest Powers trilogy lookalike offends me. It sends the message that being Asian and proud is not okay. By any standard of 21st-century human rights, is that an acceptable message to send to teenagers?

So we Asians are never going to leap to our feets, wolf-whistle, cat-call, and give rowdy standing ovations in concerts, like the mostly black audience did at the incredible Chester Children's Choir concert I attended at my school over the weekend. Our family and friend gatherings are most likely not going to spill into the streets and be full of color, noise, and spice until the wee hours of the morning. We don't yet lead in the way Western society perceives leaders: as outspoken, well-spoken, and progressive activists.

But to tell--directly or indirectly--an Asian teen that the only way he/she can have "fun," can be him- or herself, is by rejecting their Asian-ness and immersing themselves in white culture... that's plain offensive. It's inhumane.

Society--especially mostly white, American society--has made it an uphill battle for me to understand and embrace my Asian identity. As a teenager I think I would've died from happiness had there been more books with Asian characters and Asian cover models. In a world where popular media inevitably colors our perceptions of racial and ethnic acceptance, it is all the more important that something as trite ("don't judge a book by its cover") yet as monumental (covers are an important selling point for books) as book covers accurately and actively portray the truth about the world's diversity.

Sure, reading fiction can be escapism for the majority of the time. But part of what's so appealing about reading fiction is its relatability, be it contemporary realism or hardcore sci-fi/fantasy. We appreciate--nay, adore--characters whom we can understand, characters whom we can picture ourselves acting like if we were in their situation. Readers are not going to freak out if the MC of a book is of a different gender/race/ethnicity/religion/sexual orientation than them. If that happened, I'd already be wallowing in the scanty, unfortunately rather monotonous Ethnic Literature section with the likes of Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan. POC readers have long read literature featuring white protagonists...and many have enjoyed those books. Why are we assuming that white readers can't do the same? If we call for diversity, why the need to stifle important identities and physical and cultural features of a significant portion of our population?

Let's not demean YA readers' intelligences, please. When we pick up a book with a POC character and see a model of a different race on the cover, we're not going to think, "Oh, YAY! Pretty, beautiful, consumer-happy-making cover!" We are going to think, "Um, hello, did the publishing house not read the book or something? Why is there a white person on the cover when the MC is clearly Asian/black/Latino/etc.?" We're not stupid. We're not unobservant. Give us more credit than that.

Let's have covers and stories that more accurately portray the wide range of beautiful, unique, talented, smart, funny, and, yes, weird people in our world. You want to continue to earn more money, industry people? You want people to continue to love reading, to continue to buy books? Then enter the 21st century and embrace CHANGE, like every single industry and organization out there needs to be doing. Cookie-cutter Wonderbreadland white characters and settings are no longer cutting it. Books should help expand our worldview, not stifle it. The 20th century was full of progress in the human rights field: integration of schools, businesses, and facilities; affirmative action; opening old and prestigious colleges and universities to women.

Let's not take steps backward now.

[Note: This post was inspired by Ari at Reading in Color, who wrote a frustratingly sad post about the Silver Phoenix cover change. Head over to her post to find more links to similar posts written by other bloggers.]

-

Readers: If you are comfortable doing so, please feel free to share your experience with racism either here or in your own post. I welcome your comments, whether you agree or disagree with me. I don't really care what the details of your own opinions on this issue are: it's more important that people talk about this in any degree, and continue talking about it.

Monday, April 26, 2010

What's Missing In YA Lit? The Contemporary Edition

One of the side effects of blogging, especially if you're blogging with being an aspiring writer in mind, is that you start to notice trends, of what's overdone, what's missing, things that worked for you, things that didn't.

Here are some things that I have found curiously absent in the contemporary YA books I've read, and would love to see more of:

|

| whatwillmatter.com |

This has been explored over and over again: notable essays on the topic are the April 1 New York Times article and the brilliant breakdown of parental archetypes by the First Novels Club. While I still generally do have problems with any time the NYT attempts to talk about YA lit (this one's not that ignorant or outdated, but the writer is still coming from the point of view of a rather hoity-toity "literary" adult. Can they get someone who actually knows what teenagers are thinking about, please?), it was still an interesting read. I'm not sure I agree with their point that problem parents are a literary norm at odds with society, but I do agree that more recent YA lit has lessened the impact of parents on teenagers' lives.

But still. Where are the parents? Why are 90% of parents either single, divorced, dead, workaholics, etc.? I understand that a little over 50% of married couples now divorce, but I'm also curious, because the writers of these problem parents are usually in stable, happy marriages themselves. (I read your acknowledgments page. Don't try to worm out of this one.) I think it's easy to exaggerate or categorize parents into flawed archetypes because that's the way teenagers think of their parents, for the most part. But it doesn't mean that the parents have to be truly awful people. The problem parent arises in the teenage protagonist's perception of his or her parents, not necessarily in the parents themselves. It's a subtle difference, but one that I would love to see explored more in YA lit.

Some favorite parents, or stories of parents: Audrey's hilarious parents in Robin Benway's Audrey, Wait! Sarah Dessen's parent-daughter relationships (I don't care if SD's parents have practically become an archetype in themselves, they're so well done in their ambiguity of who is right and who is wrong).

| messiah.edu |

Where's the YA lit in YA lit? Most of us like to read about characters that we can relate to in some way or another. We readers read tons of YA, but have you ever noticed how little YA the characters in YA books actually read? When literature is brought up, it's usually classics (Bella's love of Austen and Bronte in Twilight), YA classics (Judy Blume's Forever plays a central role in Tanya Lee Stone's A Bad Boy Can Be Good for a Girl), or conspicuously obscure translations of European philosophers' works (I can't even give an example for this one). How cool would it be to read about a girl who reads the same type of stuff we do? If authors refer to one another within their own texts? I think it'd be absolutely fantastic if an MC read, say, the Mortal Instruments trilogy, or, for a more unisex taste, if the MC and the love interest got into a (spoiler-free, of course) discussion about The Hunger Games. Can you see that happening?

If you're worried about contemporary YA literary references dating a work, keep in mind that so many authors like to have their characters interested in pop culture, or have a particular taste in indie music. What's so different if characters were YA bookworms? I'd totally be up for that. The same way zillions of readers have picked up Pride and Prejudice, Wuthering Heights, and Romeo and Juliet from Bella Swan's love for them (and thanks to HarperTeen's exceedingly Twilight-y rejacketed reprints), or the same way I sometimes take music recommendations from book characters, I'd love to take book recommendations from characters as well. If we YAers are constantly working towards and fighting for YA lit's acceptance as "real literature" in today's society, shouldn't YA characters be a model YA bookworm?

YA books that contain YA lit: Lindsay Eland's Scones and Sensibility, which, alright, deals with two classics (Pride and Prejudice and Anne of Green Gables), but I loved how her obsession with those two drove her character. Aaaaaand I can't think of any more.

3. Homework

This is similar to the topic before this. Why, why, why do characters never have to do homework? They can be in 3 APs, 4 Honors classes, and get into some swankified Ivy League school... and yet we never see them hard at work. Instead, they spend 3-6pm at the mall, commiserating with their best friend over the guy who broke her heart over the past weekend's party. Then, when they go home, they go online, chat with their crush. Freak out. Call BFF for support and in-depth analysis of IMs. Get in bed by 10.

In bed by 10? And you're able to get into an Ivy League school? Excuse me, but from personal experience, that's impossible. For me, getting to sleep by midnight was a real miracle. There is no way an Honors student can get 8 hours of sleep every night and still get into said swankified colleges without a significant portion of their life dedicated to schoolwork and extracurricular activities. Sad but true. (And no, you cannot get into a top-tier college on grades alone. Just ask any Honors student.) I enjoy the drama the MCs face, and the conversations they have with their best friends, and the hours upon hours they can spend on spontaneous road trips with their crushes or whatever. It just...can't happen.

I know, I know that we don't read fiction to get a play-by-play of reality, but I still think it'd be nice to have hints of heavy loads of homework, all-nighters, baggy eyes, and canceled plans due to academics in YA lit.

Books with realistic portrayals of academics: Robin Brande's Fat Cat. Cat spends lots of time working on her science project. Granted, it's what drives the plot of the novel, but you can see telltale signs of her intelligence (in the effortlessness of her narration) and hard work (late nights are mentioned).

Speaking of which...

|

| education-portal.com |

Here are some basic facts: the Early Decision deadline (for academically competitive colleges, which are what many characters aim for and, miraculously, all get into) is between Nov. 1-15, notification date is a few days after Dec. 15. Early Decision means it's binding: the character can't decide to change his/her mind without financial ramifications. Regular Decision deadline is between Dec. 31-Jan. 2. And no, academically competitive colleges (like Dartmouth) will not accept--and admit--applicants after the deadline *coughBellaSwancough*. RD notifications come between mid-March and mid-April; by May 1, you have to have made your decision. Also, IVY LEAGUE SCHOOLS (and D2 and D3 schools) DON'T GIVE OUT ACADEMIC OR ATHLETIC SCHOLARSHIPS.

So can we not have characters still applying to, like, Columbia or Brown in February? Or finding out, belatedly, that they had gotten into their dream school, after everyone else has had to turn in their college decisions? Or getting a full-ride soccer scholarship to Harvard? Maybe this is a small pet peeve of mine, but the college application process quite literally sucks away all the time and energy that many academically competitive high school students have, and authors making careless mistakes such as these really puts a brake to the whole "I can relate to YA lit because I'm going through what they're going through" symbiotic relationship we want between the books and the readers.

I'd also love to read about characters going through the entirety of the college application process. It doesn't have to be a book about applying to college, but the process is such a huge part of a high school senior's life that to not talk about it in books is really to disrespect all the work that teenagers have put in to get to this point in their lives.

Books: I can think of books that show parts of the process, but none that actually get it right, unfortunately.

Books: I can think of books that show parts of the process, but none that actually get it right, unfortunately.

5. Realistic romances

I really don't want to read yet another contemporary YA book in which the shy protagonist, so full of inner turmoil is she, is suddenly pursued by a super-confident, super-cute, and super-persistent boy who *gasp* turns out to have had his eye on her for years. Can we pause for a moment here and consider how often that really happens in real life? I asked some of my friends, and, surprisingly I guess, the majority of them who are in relationships had initiated contact themselves. You heard that right. Today's women are more assertive in romance than today's men.

Now, I know that reading fiction is mostly wish fulfillment. But it can also be partly educational. Maybe I shouldn't be doing this, but when I'm really confused about life, or social situations, I sometimes try to think back on the stories I read, to see how characters in situations similar to mine had reacted. With romance, there are so few assertive female protagonists to look up to it's rather shocking. We'd all love to be the reserved and unassuming girl whose love of her life suddenly approaches her and is all, sweetheart, I've loved you for years, and I love you just the way you are, awkwardness, shyness, quirks, and all. But the probability of that happening to us? Slim to none. And not because we're extremely unlikable, but because today's love or lust doesn't work like that.

Books: I'm tired.

6. Athletes

This topic actually came up at a YA panel with Catherine Gilbert Murdock, Beth Kephart, and Rita Williams-Garcia that I attended at the Philly Book Festival a couple weekends ago. Someone told Catherine that she had heard that publishers were not very willing to publish books about athletes, especially female athletes. I'm not sure where the lady had gotten her info, and I certainly hope that publishers don't feel that way, because I personally love characters who are athletes. I don't think this is as big of an issue as the others on this list, but I enjoy how books featuring athletes do not have to be sport books, y'know?

Though I would like to see some more actual athletic action: mentions or recaps of games, practice, interactions with teammates, bus rides, the like. Basically, I'd love if YA's approach to sports (part of a character's identity, but doesn't define him/her) could be extended to other aspects of YA lit, such as race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, introvertedness, mental illness... the list goes on and on.

Athletes in books: Josie in Natasha Friend's For Keeps (varsity soccer). D.J. Schwenk in Catherine Gilbert Murdock's Dairy Queen series (super-awesome basketball player, not so great mental player).

|

| favim.com |

7. Acne (and other physical "uncomfortableness")

AudryT on Twitter suggested this to me, and I wholeheartedly agree (and am appalled that this slipped my mind initially). If acne is such a common teen nightmare, why do so many books make it a point to note characters' (particularly the MC's) clear, model-worthy skin? If the average woman is a size 14, why do more than 90% of all MCs I come across complain about their boyish figure, the way their fast metabolism makes it so that they can never put on the weight they want? Also, why do 5'6" MCs weigh only 105 pounds? Is that healthy? [ETA: So I'm not going to look up a BMI chart, but my main point is that I'd also like for there to be 5'6" MCs who weigh, say, closer to 130. Get the spectrum of body types.] I'm 5'4", size 4, and weigh far from 105 pounds. Also, I had (have) acne. Put on some muscles, girls!

I realize that teenagers are supposed to hate their bodies, no matter if your body type is the envy of someone else. But I'd love to see, say, heavier teens. Or, teens with bad skin. A lazy eye. A limp. A hearing device. An amputated leg. There are these teens out there (and bad skin and size 10 bodies are not that rare), and they (or we, in some cases) shouldn't have to feel as if they/we can't find themselves/ourselves in books.

Books: Carolyn Mackler's Love and Other Four-Letter Words. The MC's best friend in NYC does not have perfect skin. The MC in Beth Fantaskey's Jessica's Guide to Dating on the Dark Side is a size 10.

8. Characters whose differences don't identify them

The girl can be on the larger side, but it's not a book about obesity. The boy plays football, but it's not a sports book. A book with a black protagonist is not labeled as "ethnic" literature. A gay teen doesn't make a book GLBTQ lit. It's 2010: the world is a lot more diverse than literature gives it credit for. I find myself almost subconsciously looking for racial and ethnic diversity in the characters in a book. For example, are you really going to have only white, upper-middle-class friends? Protagonists don't have to be white to be understood by readers; "white" is not a default race. Having a white MC doesn't signify the MC's "lack of race": it simply means that the parameters of his/her race are normalized as to be "invisible" in society.

There's a curious disjuncture between YA and adult POC. In adult literature, POC characters are often celebrated, considered a huge accomplishment by the author in "convincingly embodying" the character's voice. Just check out an NYT bestselling list or something. Or recent books that have a good chance of being a "modern classic." In adult lit, POC is IN. Whereas in YA lit, there is still an unbalanced ratio of non-POC to POC characters. Here's to hoping for more POC "non-issue" books, and less segregation of books into "issue" (body image, self-esteem, family troubles, abuse, gang activity, etc.) and "non-issue" (light, fluffy, romance happily-ever-after, biggest problem is best friend not speaking to you).

Books: Nina Beck's This Book Isn't Fat, It's Fabulous. Justine Larbalestier's Liar.

-

I'm going to stop with the in-depth analysis here, but a quick survey on Twitter showed that this is far from a complete list. I could go on about the ones below, but I'm just going to list them quickly. Many thanks to my Twitter friends for helping add to this list, especially Carol, who said, like, half of these. :)

- Well-rounded cheerleaders and jocks - because bitchy cheerleaders and asshole jocks aren't the only types out there

- A best friend-less MC who's NOT a social leper - because I didn't (and still don't) have a BFF, and it's not because the world is unfair and I was wrongly accused of something-or-other

- Socioeconomic diversity - because I read Holly Hoxter's The Snowball Effect and realized how often books featuring blue-collar characters are often still classified as "problem novels"

- Realistic IMing/texting shorthand - U R tryin 2 hrd if U wryt lyk dis. Pls stop kthxbye.

- Male MCs - because a lot of YA readers like boys, and boy narrators are hot, and besides, we want to try to understand how their minds work

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

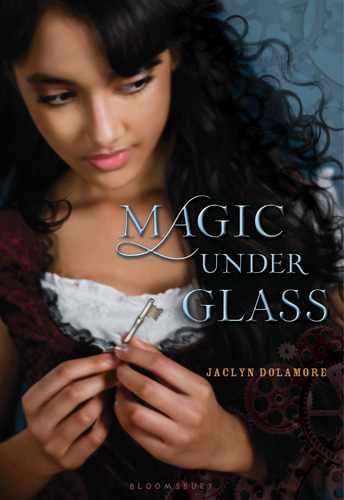

Magic Under Glass' New Cover!

I was, sadly, silent while the blogosphere and Internet was all abuzz a few weeks ago with the white-washing cover controversary surrounding Jaclyn Dolamore's debut novel, Magic Under Glass. (It was due mostly to schoolwork.) However, the new Magic Under Glass cover has been popping up now, and here it is:

Yeah, I couldn't find a bigger picture of it. Sorry! Now compare it with the original cover:

Isn't the new cover gorgeous? I really don't understand why Bloomsbury didn't just do the second cover first. While I admit that I like the lighting of the old cover, and think it would look very lovely on another book, the new one looks, on the one hand, much more professional. I mean, what was up with Number One's Photoshopped-floating-shadow translucent-title overlay? Hello?! Anyway, I digress.

Last year, I wrote a blog post about how I felt the new cover of Justine Larbalestier's Liar (changed, once again, after media outcry about its whitewashing) was...pretty, but had not gone far enough to correct the decades-old issue of whitewashing on covers. For reference, here is the cover of Liar again:

My issue with this image is that it's just too pretty, too unlike the author's descriptions of Micah in the book, too acquiescent to the majority (read: white) ideal of beauty. Because honestly? How many black girls look like this model? (How many girls of any other race, for that matter?) The supermodel-worthiness of the model, along with the "stillness" of the cover, left me dissatisfied and feeling that Bloomsbury had not done enough. No, far from it: they had simply gave themselves a lightly reprimanding slap on the wrists, and put the white majority's idealized version of black beauty on the cover.

This time, however, I think Bloomsbury's on a better track.

I'm still not completely satisfied, of course. There's still a "staticness" about these covers, a sluggishness, that conveys little movement for stories that are wide and sweeping and what have you. But I'm super happy they didn't put the teenage equivalent of Freida Pinto (Latika from Slumdog Millionaire) on the cover:

Or Aishwarya Rai (from Bride and Prejudice):

Because--do you see what I'm trying to depict here? There's no denying that Freida and Aishwarya are stunning. I don't care what race you are, or what your sexual orientation is, but there's almost no way you can NOT think either one of these ladies beautiful. Their beauty transcends almost impenetrable racial boundaries and appeals to the societal ideal of beauty.

That's why I'm much happier with the improved cover for Magic Under Glass than I was for that of Liar. On the cover of MUG is now a girl who could be my classmate, or my good friend back in high school. She's pretty too--but her beauty is so much more grounded in reality. I don't feel like a freaking ugly loser when I inevitably subconsciously compare myself to the cover of a book anymore. Like it or not, book covers do influence our impressions of a book, and now the good thing is that I can eagerly pick this book up in the store now and be allowed to think, I could be her. She could be me. I can be as brave and resourceful and beloved as she is.

And that, my friends, is an EXCELLENT thing for readers to think and feel.

So by all means, go out there and recommend this book like crazy. I bet there will be grateful girls out there, girls who are happy that finally, finally there's someone like them on the cover of a book: someone flawed, someone different, and someone amazing in their uniqueness and differences. This is one small step towards expanding society's standards of beauty, towards lowering teenage girls' insecurities over their appearances because they don't look like the only faces they see in prominent media positions. And that is a very beautiful thing.

So thank you, Bloomsbury, for this small gift. But you know what they say about the third time. Don't mess up again.

I leave you with the new MUG cover again. So you can bask in it, as I am.

Yeah, I couldn't find a bigger picture of it. Sorry! Now compare it with the original cover:

Isn't the new cover gorgeous? I really don't understand why Bloomsbury didn't just do the second cover first. While I admit that I like the lighting of the old cover, and think it would look very lovely on another book, the new one looks, on the one hand, much more professional. I mean, what was up with Number One's Photoshopped-floating-shadow translucent-title overlay? Hello?! Anyway, I digress.

Last year, I wrote a blog post about how I felt the new cover of Justine Larbalestier's Liar (changed, once again, after media outcry about its whitewashing) was...pretty, but had not gone far enough to correct the decades-old issue of whitewashing on covers. For reference, here is the cover of Liar again:

My issue with this image is that it's just too pretty, too unlike the author's descriptions of Micah in the book, too acquiescent to the majority (read: white) ideal of beauty. Because honestly? How many black girls look like this model? (How many girls of any other race, for that matter?) The supermodel-worthiness of the model, along with the "stillness" of the cover, left me dissatisfied and feeling that Bloomsbury had not done enough. No, far from it: they had simply gave themselves a lightly reprimanding slap on the wrists, and put the white majority's idealized version of black beauty on the cover.

This time, however, I think Bloomsbury's on a better track.

I'm still not completely satisfied, of course. There's still a "staticness" about these covers, a sluggishness, that conveys little movement for stories that are wide and sweeping and what have you. But I'm super happy they didn't put the teenage equivalent of Freida Pinto (Latika from Slumdog Millionaire) on the cover:

Or Aishwarya Rai (from Bride and Prejudice):

Because--do you see what I'm trying to depict here? There's no denying that Freida and Aishwarya are stunning. I don't care what race you are, or what your sexual orientation is, but there's almost no way you can NOT think either one of these ladies beautiful. Their beauty transcends almost impenetrable racial boundaries and appeals to the societal ideal of beauty.

That's why I'm much happier with the improved cover for Magic Under Glass than I was for that of Liar. On the cover of MUG is now a girl who could be my classmate, or my good friend back in high school. She's pretty too--but her beauty is so much more grounded in reality. I don't feel like a freaking ugly loser when I inevitably subconsciously compare myself to the cover of a book anymore. Like it or not, book covers do influence our impressions of a book, and now the good thing is that I can eagerly pick this book up in the store now and be allowed to think, I could be her. She could be me. I can be as brave and resourceful and beloved as she is.

And that, my friends, is an EXCELLENT thing for readers to think and feel.

So by all means, go out there and recommend this book like crazy. I bet there will be grateful girls out there, girls who are happy that finally, finally there's someone like them on the cover of a book: someone flawed, someone different, and someone amazing in their uniqueness and differences. This is one small step towards expanding society's standards of beauty, towards lowering teenage girls' insecurities over their appearances because they don't look like the only faces they see in prominent media positions. And that is a very beautiful thing.

So thank you, Bloomsbury, for this small gift. But you know what they say about the third time. Don't mess up again.

I leave you with the new MUG cover again. So you can bask in it, as I am.

Wheeeee look at me! I'm real and unique and therefore I am beautiful!!!

Friday, December 4, 2009

Discussion: Does YA Lit Belong in Classrooms?

The latest thing to stir up the YA lit and education communities is the removal of some YA books being taught alongside classics in a college preparatory English class at Montgomery County High School in Kentucky. Many of the parents and administration argue that the books are not intellectual enough to be taught in a class that's supposed to prepare intelligent and academically prone students for college. For more detail, check out the Kentucky.com article here.

Now, a blogger by the name of Martin has been posting about the issue. His first post on Monday was titled The Banning of Academic Rigor: Anti-censorship groups now calling enforcement of curriculum standards "censorship", in which he argued that "popular teen books" have should not be given the same academic consideration as canonized classics such as Dostoyevsky, Conrad, James, and Steinbeck because they discuss "petty" things such as high school dating, zits, puberty, and crushes. His next related post, Do you have to have read a book to say anything about it at all? More on the Montgomery County "censorship" case, further stresses the fact that students in college prep courses should not waste their time with teen literature, focusing instead on the classics for collegiate preparation, and that students who require modern, popular, or teen literature to be engaged in class do not belong in a college prep class in the first place. His running argument is that classics have withstood the test of time and have been given the thumbs-up from millions of people over decades; why should we even bother with books whose literary presence may be virtually nonexistent in five years?

I read blog posts like Martin's because I like to see where both sides of the debate are coming from before presenting my own arguments. It's important to surround yourself with people who share your opinions, beliefs, and values, but it is just as important to open yourself up to the incendiary feelings and indignation caused by hearing the other side. Too often I read or hear heated comments made in the moment by offended debators who have not stopped to seriously consider the other side's argument, and who construct their own comments in ways that lend no support or credibility to their own side. The best debators succeed because they know their opponent almost as well as they do themselves, which is why I urge you all to read as much as you can about both sides of this argument, to fully see what part you may play in the debate. Those who believe that YA books do not belong in the classroom are not our "enemies:" our job is not to talk trash about them or yell at them. Our goal is to promote open-mindedness and an acknowledgement that our side is as equally justified as theirs. Closed minds, not groups or individuals with opposing beliefs, are our "enemy," and that goes for both sides of the debate.

Educator E. D. Hirsch, author of the What Your # Grader Needs to Know series, believes that everyone should be given a solid foundation of common knowledge to draw from, and I agree to an extent. Where would we (and by "we" I mean Americans in this instance) be if we did not all understand the conception and evolution of the Constitution? if people did not know for what reason the Civil War was fought? if no one had at least a basic knowledge of Shakespeare and what he wrote? if the times tables, addition, subtraction, and how to calculate interest were not essential knowledge?

It is along those lines that we do have a literary canon, a list of essential works that we encourage all students to have some information on. It would be nice if everyone got to read all of those books, but, like Martin said, one does not necessarily have to read the book in its entirety to grasp its meaning. I highly doubt I'm going to read another Steinbeck book, and I sure as heck didn't finish Heart of Darkness because it almost literally gave me stomach ulcers, it was so painful to stomach, but hey, I get the gist. I know that the whale in Moby Dick stands for something-something lalala. I know that Henry James ushered in a new era in writing style and themes. And I know that Brave New World and 1984 are dystopian novels (though I will forever call into question Huxley's writing ability).

So now we've established that there is a literary canon that most people should be aware of, and that school is a really good place to learn about those works. However, the most common misconception of schools is that education is completely separate from the real world. Tradition has established that there be an established basic curriculum that schools must cover, relevance be damned. Most tests do not measure retention and comprehension; that is why so many students can--and do--cram for tests, only to forget everything they ever learned about that subject within 24 hours of taking the test. That is why standardized tests such as the SAT have their worth constantly being called into question. What is it measuring? Academic aptitude--or a student's aptitude in cramming strategies? Intellectual achievement--or the level of a kid's achieving temporary absorption of the strategies needed to take the test? No--at this point the A in SAT stands for nothing, which is kind of darkly amusing and indicative.

Why should an institution that has so much responsibility and influence over a child's upbringing be thus detached from real world application? An appallingly high percentage of students nowadays find school completely useless. My own brother's educational mantra has become, "Why are we even studying this anyway? I have no use for this." We have been brought up with the belief that the literary canon is something that we all should know--but along the way, we forgot why it's important, why it was canonized. Why, it's important because many people over the years have said so! one may argue. It was canonized because it withstood the test of time! Well...uh....yeah, but why did it withstand the test of time?

It's not a problem with the texts, people like Martin would then say, but rather a problem with the way the teacher is presenting the material. Perhaps. I don't deny that there are some awful teachers out there who don't deserve their tenure or their positions. But when the majority of students out there find their English class required reading lists irrelevant, then we must overhaul our thinking of the educational system. We cannot simply assume that students in college prep classes are in those classes because they understand, appreciate, and like the material. Do you realize how many students out there unwillingly force themselves into Honors and AP classes because they've had it drilled into their heads by all facets of society that if they don't get on the college prep track, they will never get into a good college and thus will not succeed in life? Hidi & Renninger have done extensive research on the relationship between interest, motivation, and expression of interest, and their four-phase model of interest development is as follows:

The goal of education is not to create armies of zombies who acquiesce to the status quo and, while transcribing corporate documents or crunching numbers, believe that the way things were and are is the way things should be forever. Education is not a field of study similar to math and most sciences, where, once something is proven to be true, it can remain as fact for hundreds of years, and maybe even for all time. Even educational practices in place five years ago seem woefully out of date today. In education, success does not mean adherence to traditional methods. It means bringing out the best in each student. Acknowledging that there are individual as well as generational differences. Fostering a mind open to change and new ideas. Education equals change, and we want students to ask questions, to speak up if they disagree with something, and to accept that there are different sides to every story.

Smartly chosen YA books close the gap between school and real life, and encourage students to make connections and to take personal interest in things. Read the classics alone, discuss them within the context of the classroom, and students are more likely to feel apathetic about the works, dispassionate about reading and learning in general. Read the classics alongside similar contemporary works that are relevant to students' lives and feelings, and suddenly the "old" stuff takes on significance. I'm not a Shakespeare fan, yet I am constantly surprised and impressed at the many ways in which Shakespeare has manifested itself into our modern culture, without our knowledge.

A huge mistake is in assuming that only those works that have withstood the test of time are worth studying. This gives students the impression that childhood, schooling, and adolescence are only preparations for the Ultimate Crowning Glory of Adulthood, and that you have to be old to make a difference. Contemporary YA lit shows these students that it's okay to feel all those teenage insecurities and make those mistakes that seem awful the day after, but become fodder for laughter in a few months. Those who oppose YA lit trivialize the intelligence of teenagers, and those teens that have been bombarded with this kind of thinking grow up to be either the close-minded, loud-mouthed adults who believe that the success of their passage through adolescence makes everything they say the only way things can be, or else they become the feeble workers with the hunched corners sitting in corners and always fearing to speak up.

There is the mistaken association that things related to teens = bad/unimportant/valueless, and that contemporary books = low-quality/fluff/garbage. There is also the impression that the only books that belong in academia are those with "adult" themes, chosen by adults who believe their children should learn the things and the way they did. I think the biggest--and most important--voice missing from this debate, however, is the voice of those Kentucky high school students in Risha Mullins' class. What did they gain from the inclusion of YA texts on their reading lists? If they found that the "contemporary teen books," as Martin says so disdainfully, have actually bettered their relationship with and understanding of the classics and learning, then that's really all the data you need. YA literature is not attempting to lower the quality of literature; rather, considered in conjunction with canonized works, it may serve to enhance the reading and learning experience.

It's high time that the adults who have been the ones constructing curriculum requirements and composing the required reading lists take a step back, and allow the opinions and desires of the students to be heard. After all, progress in education means change, and who better than those whom we are trying to educate to become the change-makers of the present and future?

Now, a blogger by the name of Martin has been posting about the issue. His first post on Monday was titled The Banning of Academic Rigor: Anti-censorship groups now calling enforcement of curriculum standards "censorship", in which he argued that "popular teen books" have should not be given the same academic consideration as canonized classics such as Dostoyevsky, Conrad, James, and Steinbeck because they discuss "petty" things such as high school dating, zits, puberty, and crushes. His next related post, Do you have to have read a book to say anything about it at all? More on the Montgomery County "censorship" case, further stresses the fact that students in college prep courses should not waste their time with teen literature, focusing instead on the classics for collegiate preparation, and that students who require modern, popular, or teen literature to be engaged in class do not belong in a college prep class in the first place. His running argument is that classics have withstood the test of time and have been given the thumbs-up from millions of people over decades; why should we even bother with books whose literary presence may be virtually nonexistent in five years?

I read blog posts like Martin's because I like to see where both sides of the debate are coming from before presenting my own arguments. It's important to surround yourself with people who share your opinions, beliefs, and values, but it is just as important to open yourself up to the incendiary feelings and indignation caused by hearing the other side. Too often I read or hear heated comments made in the moment by offended debators who have not stopped to seriously consider the other side's argument, and who construct their own comments in ways that lend no support or credibility to their own side. The best debators succeed because they know their opponent almost as well as they do themselves, which is why I urge you all to read as much as you can about both sides of this argument, to fully see what part you may play in the debate. Those who believe that YA books do not belong in the classroom are not our "enemies:" our job is not to talk trash about them or yell at them. Our goal is to promote open-mindedness and an acknowledgement that our side is as equally justified as theirs. Closed minds, not groups or individuals with opposing beliefs, are our "enemy," and that goes for both sides of the debate.

Educator E. D. Hirsch, author of the What Your # Grader Needs to Know series, believes that everyone should be given a solid foundation of common knowledge to draw from, and I agree to an extent. Where would we (and by "we" I mean Americans in this instance) be if we did not all understand the conception and evolution of the Constitution? if people did not know for what reason the Civil War was fought? if no one had at least a basic knowledge of Shakespeare and what he wrote? if the times tables, addition, subtraction, and how to calculate interest were not essential knowledge?

It is along those lines that we do have a literary canon, a list of essential works that we encourage all students to have some information on. It would be nice if everyone got to read all of those books, but, like Martin said, one does not necessarily have to read the book in its entirety to grasp its meaning. I highly doubt I'm going to read another Steinbeck book, and I sure as heck didn't finish Heart of Darkness because it almost literally gave me stomach ulcers, it was so painful to stomach, but hey, I get the gist. I know that the whale in Moby Dick stands for something-something lalala. I know that Henry James ushered in a new era in writing style and themes. And I know that Brave New World and 1984 are dystopian novels (though I will forever call into question Huxley's writing ability).

So now we've established that there is a literary canon that most people should be aware of, and that school is a really good place to learn about those works. However, the most common misconception of schools is that education is completely separate from the real world. Tradition has established that there be an established basic curriculum that schools must cover, relevance be damned. Most tests do not measure retention and comprehension; that is why so many students can--and do--cram for tests, only to forget everything they ever learned about that subject within 24 hours of taking the test. That is why standardized tests such as the SAT have their worth constantly being called into question. What is it measuring? Academic aptitude--or a student's aptitude in cramming strategies? Intellectual achievement--or the level of a kid's achieving temporary absorption of the strategies needed to take the test? No--at this point the A in SAT stands for nothing, which is kind of darkly amusing and indicative.

Why should an institution that has so much responsibility and influence over a child's upbringing be thus detached from real world application? An appallingly high percentage of students nowadays find school completely useless. My own brother's educational mantra has become, "Why are we even studying this anyway? I have no use for this." We have been brought up with the belief that the literary canon is something that we all should know--but along the way, we forgot why it's important, why it was canonized. Why, it's important because many people over the years have said so! one may argue. It was canonized because it withstood the test of time! Well...uh....yeah, but why did it withstand the test of time?

It's not a problem with the texts, people like Martin would then say, but rather a problem with the way the teacher is presenting the material. Perhaps. I don't deny that there are some awful teachers out there who don't deserve their tenure or their positions. But when the majority of students out there find their English class required reading lists irrelevant, then we must overhaul our thinking of the educational system. We cannot simply assume that students in college prep classes are in those classes because they understand, appreciate, and like the material. Do you realize how many students out there unwillingly force themselves into Honors and AP classes because they've had it drilled into their heads by all facets of society that if they don't get on the college prep track, they will never get into a good college and thus will not succeed in life? Hidi & Renninger have done extensive research on the relationship between interest, motivation, and expression of interest, and their four-phase model of interest development is as follows:

- triggered situational interest

- maintained situational interest

- emerging individual interest

- well-developed individual interest

The goal of education is not to create armies of zombies who acquiesce to the status quo and, while transcribing corporate documents or crunching numbers, believe that the way things were and are is the way things should be forever. Education is not a field of study similar to math and most sciences, where, once something is proven to be true, it can remain as fact for hundreds of years, and maybe even for all time. Even educational practices in place five years ago seem woefully out of date today. In education, success does not mean adherence to traditional methods. It means bringing out the best in each student. Acknowledging that there are individual as well as generational differences. Fostering a mind open to change and new ideas. Education equals change, and we want students to ask questions, to speak up if they disagree with something, and to accept that there are different sides to every story.

Smartly chosen YA books close the gap between school and real life, and encourage students to make connections and to take personal interest in things. Read the classics alone, discuss them within the context of the classroom, and students are more likely to feel apathetic about the works, dispassionate about reading and learning in general. Read the classics alongside similar contemporary works that are relevant to students' lives and feelings, and suddenly the "old" stuff takes on significance. I'm not a Shakespeare fan, yet I am constantly surprised and impressed at the many ways in which Shakespeare has manifested itself into our modern culture, without our knowledge.

A huge mistake is in assuming that only those works that have withstood the test of time are worth studying. This gives students the impression that childhood, schooling, and adolescence are only preparations for the Ultimate Crowning Glory of Adulthood, and that you have to be old to make a difference. Contemporary YA lit shows these students that it's okay to feel all those teenage insecurities and make those mistakes that seem awful the day after, but become fodder for laughter in a few months. Those who oppose YA lit trivialize the intelligence of teenagers, and those teens that have been bombarded with this kind of thinking grow up to be either the close-minded, loud-mouthed adults who believe that the success of their passage through adolescence makes everything they say the only way things can be, or else they become the feeble workers with the hunched corners sitting in corners and always fearing to speak up.

There is the mistaken association that things related to teens = bad/unimportant/valueless, and that contemporary books = low-quality/fluff/garbage. There is also the impression that the only books that belong in academia are those with "adult" themes, chosen by adults who believe their children should learn the things and the way they did. I think the biggest--and most important--voice missing from this debate, however, is the voice of those Kentucky high school students in Risha Mullins' class. What did they gain from the inclusion of YA texts on their reading lists? If they found that the "contemporary teen books," as Martin says so disdainfully, have actually bettered their relationship with and understanding of the classics and learning, then that's really all the data you need. YA literature is not attempting to lower the quality of literature; rather, considered in conjunction with canonized works, it may serve to enhance the reading and learning experience.

It's high time that the adults who have been the ones constructing curriculum requirements and composing the required reading lists take a step back, and allow the opinions and desires of the students to be heard. After all, progress in education means change, and who better than those whom we are trying to educate to become the change-makers of the present and future?

Saturday, August 15, 2009

Discussion: Is the New LIAR Cover Not Enough?

As most of you know by now, last week's big news was publishing giant Bloomsbury's announcement that they were changing the original cover of Justine Larbalestier's YA psychological thriller, LIAR, into something more representative of Justine's intentions for Micah, the protagonist. The original cover featured a white-looking girl with long, smooth tresses--when Micah is described as being racially mixed, with nappy black hair. The new cover, unveiled last week, looks like this:

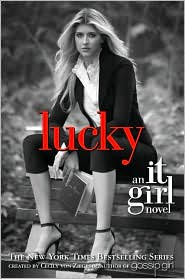

I feel like many readers read books with one of two goals in mind: they want to escape into another, fully realized world, or else they want to find a story that resonates with them, that they can relate to. Either way, one of the most important things is our ability to believe in the MC as a real person, complete with complexities, contradictions, passions, and vulnerabilities. Books like the Gossip Girl or A-List series may be great guilty-pleasure reads, but I doubt that many people read these books and go, wow, I can really relate to / want to be / can see myself in [insert bitchy, beautiful, and tormented character name here]!

I feel like many readers read books with one of two goals in mind: they want to escape into another, fully realized world, or else they want to find a story that resonates with them, that they can relate to. Either way, one of the most important things is our ability to believe in the MC as a real person, complete with complexities, contradictions, passions, and vulnerabilities. Books like the Gossip Girl or A-List series may be great guilty-pleasure reads, but I doubt that many people read these books and go, wow, I can really relate to / want to be / can see myself in [insert bitchy, beautiful, and tormented character name here]!

When Bloomsbury replaced the white face that once stood on the cover, they replaced it with an image of beauty that the white, mainstream population considers acceptably beautiful. It's the tactless equivalent of darkening a mainstream model's skin using PhotoShop: there is still something "truthful" missing from this cover. We are still using the "white" standards of beauty for the cover.

When Bloomsbury replaced the white face that once stood on the cover, they replaced it with an image of beauty that the white, mainstream population considers acceptably beautiful. It's the tactless equivalent of darkening a mainstream model's skin using PhotoShop: there is still something "truthful" missing from this cover. We are still using the "white" standards of beauty for the cover.

Bloggers, readers, authors, and other members of the reading world clamored for a black face on the cover. Well, we got a black face... but one that is still one that conforms to the status quo. It's a step in the right direction, but in the end, it's not enough. It may even be a cop-out.

A vast improvement over the original, right? The model's race is now consistent with the main character's. When Justine posted the picture on her blog, people went wild with praise. Many are in love with this beautiful cover.

It's beautiful, yes, there's no doubt about it. The girl has the kind of inhuman beauty that makes us hate yet worship supermodels at the same time. And oh yes, it's quite wonderful that the model's race now matches the race that Justine intended Micah to be.

But when my first reaction upon seeing this cover was, "Oh. Ah... well... ah... okay, I guess."

Shocked? Horrified? Incensed at my less-than-passionate response to the new cover? Let me try to explain why I feel this way.

I feel like many readers read books with one of two goals in mind: they want to escape into another, fully realized world, or else they want to find a story that resonates with them, that they can relate to. Either way, one of the most important things is our ability to believe in the MC as a real person, complete with complexities, contradictions, passions, and vulnerabilities. Books like the Gossip Girl or A-List series may be great guilty-pleasure reads, but I doubt that many people read these books and go, wow, I can really relate to / want to be / can see myself in [insert bitchy, beautiful, and tormented character name here]!

I feel like many readers read books with one of two goals in mind: they want to escape into another, fully realized world, or else they want to find a story that resonates with them, that they can relate to. Either way, one of the most important things is our ability to believe in the MC as a real person, complete with complexities, contradictions, passions, and vulnerabilities. Books like the Gossip Girl or A-List series may be great guilty-pleasure reads, but I doubt that many people read these books and go, wow, I can really relate to / want to be / can see myself in [insert bitchy, beautiful, and tormented character name here]!In the same way, a book's cover influences the way we perceive the story and characters, whether that is the author and publisher's intentions or not. A cover should aim to reflect the overall mood of the book, if not to provide us with a minutely accurate photograph of what the MC looks like (because every person's preception of the book's MC is slightly different).